|

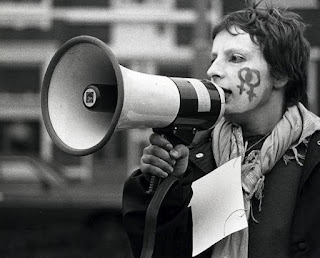

| (c) Netherlands Nationaal Archief (2009), FlickR |

As I have reported previously on my blog [here, here, here] and in other media and forums [EJIL Talk!, "Die Presse", jusPortal.at], the Human Rights Council has made the significant step to confirm the technological neutrality of human rights protection regimes in the easy to remember phrase that "the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online".

As I have argued, we're not out of the woods yet, because there remain serious questions to be answered. For one, how to operationalize this commitment.

Another interesting question is whether there exist human rights protection gaps. De facto, they do. De jure, they shouldn't . They exist de facto in the sense that not all human activity online that should be protected is protected by courts because they lag behind in applying human rights comprehensively and sensibily online.

Indeed, since "the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online", any online gaps can be filled by interpreting existing human rights in a technology-sensitive way.

An interesting case in point is the question whether there is an online equivalent to the right to offline assembly.

Of course, the right to assembly is well protected by international law, and the right to access the Internet can be seen as a precondition to exercise the right to assembly offline in a meaningful way under the conditions of the information society. One motivation of Egyptian authorities in January 2011 for shutting down the Internet was, in fact, that civil society and opposition members should not be able to coordinate meetings. Of course, this backfired.

But let's look at the online dimension of the right to assembly more closely.

In the May 2012 final report of the 5th initiative [in German] of the Internet&Society Co:llaboratory, my colleagues and I queried whether virtual sit-ins should be covered by the right to assembly. The right to offline assembly can only be exercised under certain conditions (prior announcement, for one, and must meet certain limitations regarding length and duration). There is nothing that makes me think that we could not apply similar conditions to exercising the online freedom of assembly. Indeed, the three part test that we now from international human rights law should be applied mutatis mutandis: legality of interference, legitimacy of goal pursued by the interference, and proportionality of interference.

How would this look like?

One way to exercise the online right to assembly would be virtual sit-ins, or online demonstrations, which take the form of repeated service queries by individuals to a particular server which may result in a slowing down of the reponse speed of that server to other non-involved queries or even make the server crash entirely.

In that case we would speak of a DDoS attack, which will most likely not be covered by the right to assembly, while certain inconveniences for other users might still be. Just think of the following: Isn't it covered by the human right to offline assembly that it becomes a bit more difficult to enter a specific shop on a certain street at a specific time? My answer would be a clear yes, while to the legality of shutting down a shop completely my answer would be a clear no.

Of course, there are grey areas, but the German government might just shed some light on the issue for us.

Internet&Society Co:llaboratory expert Jeannine pointed out to me a query of the left-wing political group "Die Linke" in the German Bundestag in which the MPs asked the government to collect information on the prosecution of teenagers who had participated, in June 2012, in a virtual protest action against the German music industry rights management company GEMA.

The MPs argued that the action was not "Computersabotage" (computer sabotage, as penalized by the German Criminal Code), but rather a „eine Protestaktion, die die Kriterien einer Onlinedemonstration erfüllt“ ["a protest, that meets the criteria for online demonstrations"].

The original query [in German] makes for interesting reading.

Of course, the "criteria for online demonstrations" are far from clear.

But this is exactly what I (and others) predicted would happen. We have the commitment to the applicability of human rights online. We now need to hammer out what this means in practice. Cases such as this will help us gain a more nuanced understanding.

Let's scrutinize them closely.